Bethwin Road: a remarkable history

Rory O’Connell traces the history of 59 Bethwin Road, from 1870s ‘clergy house’ – through war and redevelopment – to Kairos residential rehab. Since 1997, it’s been home at any one time to 16 men and women in recovery.

“In the middle of this area is a strange group of streets hemmed in on one side by the railway and entered only here and there on the other three sides like a fortress through its gates. The impression made upon me by this block of streets, when I first I walked through them was never to be forgotten. They are in some ways without counterpart in London. There are places more squalid, and there may be people more debased, but there are none whereon the word ‘outcast’ is so deeply branded.”

— Life and Labour of the People of London, Charles Booth, Vol 6 1903

The northern boundary of this group of streets so vividly described in Booth’s survey and coloured the darkest blue on the accompanying ‘poverty map’ was Avenue Road, Walworth, later to be renamed Bethwin Road. Prominent on Avenue Road and built just over 20 years earlier was the vicarage of the parish that served this impoverished district, St Michael and All the Angels. This was the building that, nearly 100 years after Booth wrote those words, would become the first proper home and treatment centre of Kairos Community Trust.

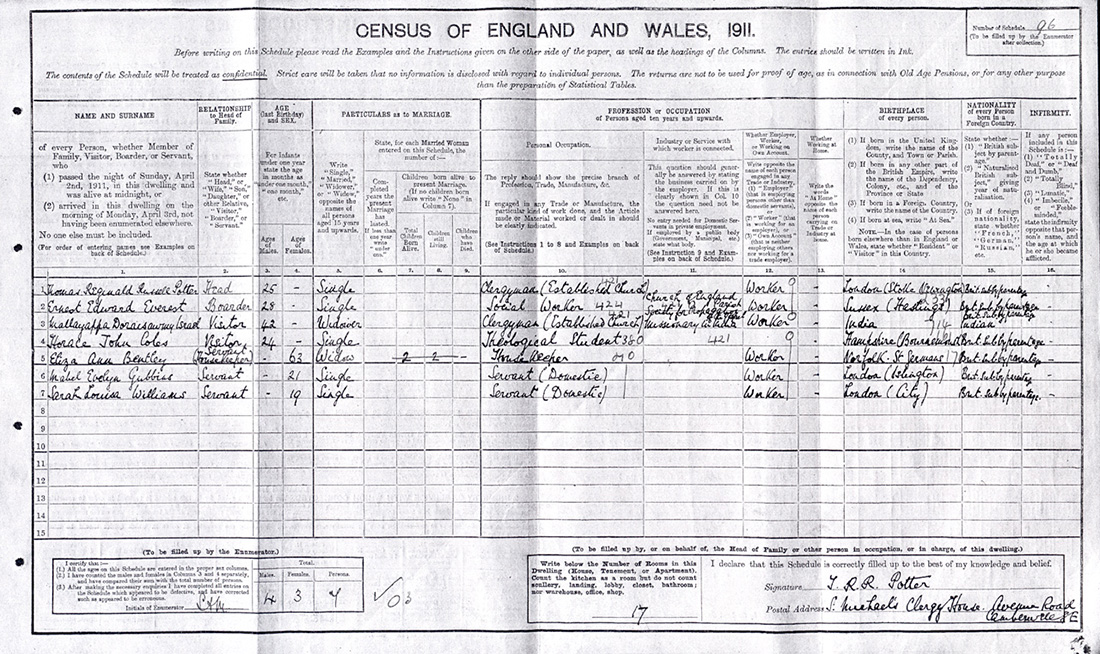

The census of 1881 does not list the detailed occupants of number 59 , then called the ‘clergy house’, but the commercial Kelly’s directory lists three clergymen, a small number for what was a substantial dwelling of 17 rooms in a densely populated but thriving Victorian enclave. The census does though reveal incredible detail of the occupants of the neighbouring houses and streets such as Toulon Street, Sultan Street and Avenue Cottages, including three pubs within a few hundred yards.

The houses were typically overcrowded, with the census often showing three families per house in Avenue Road and the cottages opening off it. The majority were classed as what would be called semi- or un-skilled, with frequent occurrence of painters, cabinet-makers and all the building trades as well as charwomen, seamstresses and servants, brewer and ‘potmen’. Their origins or places of birth listed in 1881 are remarkably parochial for a part of London that was reportedly dominated by Irish immigrants, many being born within the borough of Camberwell or nearby Walworth (the current London Borough of Southwark being formed later in the 20th century).

This census record (above) from the 1911 Census conducted on 2 April, the last for which detailed information is available (and the last before the First World War), shows that the large house is still relatively under-occupied with the Reverend Thomas Potter, aged 25, the sole clergyman along with a ‘social worker’, a visiting missionary from India and a theological student. A housekeeper and two maids completed the household.

Although Booth described the appalling conditions at the turn of the century, it was not until the mid-1930s that the whole area was officially condemned as slums, and photographs show the conditions around the church and vicarage of Avenue Road, which was renamed Bethwin Road, after a local farm, in 1936 as part of the clearance.

The Church had already given Kairos a helping hand in providing the first premises for the Kilburn Night Shelter, which moved to three disused houses in Stonhouse Street a stone’s throw from Clapham Common tube. It was here that Fr John Kitchen, along with a core of volunteers who would become lifelong workers and supporters of Kairos, engaged in a range of services for the local homeless community, with accommodation for four people, a kitchen and dining room for drop-in homeless people and, eventually, the first Kairos shop.

The Second World War bombing contributed to much wider destruction of the local area although 59 was undamaged. Post-war reconstruction would eventually lead to building of the towers of the Brandon Estate to the north from 1958 and the even taller Wyndham Estate to the south in the 1960s.

The impact on the Church and its activities was considerable, the parish became amalgamated, the original church was demolished in 1972 and eventually, with just 51 attending parishioners, was absorbed into the local secondary school, sharing the school gym for Sunday worship. It was in these circumstances in 1997 that the vicarage, by now too large and expensive to maintain, became available for Kairos to purchase.

The end of the Church of England’s association with number 59 was not insignificant in church history, however: the outgoing Vicar the Rev Pat Vowles becoming the first woman priest in the diocese of Southwark in 1994, who also continued her support for Kairos in subsequent years.

However, with the inroads into regular daily care and support for a core of homeless people using Stonhouse Street, ambitions were growing that could only really be developed elsewhere.

“We needed a way to try to help people that was more structured… We realised we needed a rehabilitation centre where therapy was the main process. And acquiring Bethwin Road enabled us to do that,” explained Fr John Kitchen.

When the Church made the decision to sell the Stonhouse Street houses they again came to the rescue, alerting Kairos to the availability of the now redundant vicarage at 59. By this time it had become an unofficial if amiable squat, and the original coach house had become home to the Blue Elephant Theatre, whose director was installed in the house. With the assistance of a grant from the National Lottery, Kairos finally purchased the building outright and the first manager, Mossie Lyons, and four volunteers moved in in October 1997.

After objections had been lodged against Kairos using the house as a treatment centre, many local people were won over at a lively public meeting and Kairos was finally able to occupy the whole house and operations could commence with relatively few changes required.

With openness, trust and well-being being central to the purpose of the building, the large single front door, the spacious ground floor meeting room, dining room and kitchen needed little alteration. All these rooms were centred around the imposing staircase leading to the shared bedrooms, another distinguishing feature of the house when most centres were graduating towards the privacy of single and en-suite rooms. Food, cooked daily by and for the residents, was a key part of Bethwin from the start.

The physical form of the building also lent itself to the needs of a safe therapeutic environment in other ways. As an astute observer of the newly acquired building noted, “there are no corridors in Bethwin. The three floors of the house offered natural division between eating, sleeping and treating.”

From the outset, treatment at Bethwin Road was explicitly committed to the 12-step programme of AA. Established at the foundation of Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935, the ‘steps’ offered a unique approach to achieving and maintaining sobriety. The aim at Bethwin was – and still is – for residents to reach Step 3 of the programme within 12 weeks, and required attendance at a minimum of three AA meetings a week. This would be achieved using group therapy, handwritten step-work and regular one-to-ones with experienced counsellors, who had completed the steps themselves. A weekly in-house AA meeting was established (and later Narcotics Anonymous, monthly) to run independently of the Kairos programme, on AA terms.

“Our hope is that when a client leaves, they can make a more informed choice about how they will meet their needs in the future and embrace the responsibility that comes with ongoing recovery.”

— Lee Slater, Manager, Bethwin Road

* * *

The relationship of the house, the church, the neighbourhood around Bethwin Road and Kairos (there has been a continuity of social purpose of the house from its beginnings to the present day) could be summarised by the vicar of parish the Revd Jonathan Roberts, speaking in 2018:

“The house was built to be a base for ministry in very tough part of Victorian London. Charles Booth’s survey of the ‘Life and Labour of the People of London’ described much of the Southwark diocese as ‘the largest area of unbroken poverty in any city in the world’. This part of Camberwell particularly was an area that was a massive social challenge to Christians and there were several projects set up in the area.

“So, the Bethwin house was designed to support people working in a tough, polluted and overcrowded poor slum area. The bombing in 1940 and then again in 1944-5 cleared terrible conditions for the rebuilding of the following 30 years. It is great that it is still used for a group of people and that it is there to help.”

- Special thanks to the staff of Southwark Local History Library and Rev Stephen Roberts, Steve Grindlay and current and former Kairos staff for additional information.